1.1 Time-underemployment indicator 1: Involuntary part-time

People in employment can work either full-time or part-time. A part-time worker is someone who works fewer hours than a full-time worker. In the UK there is no specific number of hours that makes someone full or part-time, and the full-time/part-time threshold is debated, but a full-time worker will usually work 30 or 35 hours or more a week (Government n.d.). In the UK Labour Force Survey, the split between full-time and part-time employment is based on respondents’ self-classification (ONS 2023). The average hours worked by part-timers, for all the periods included in this analysis, is 20 hours.

Part-time jobs are of lower quality (including being lower paid) than full-time jobs, on the whole, and they bring a range of career penalties (ILO 2013a; Nightingale 2019; Warren and Lyonette 2018). Yet part-time employment is extensive in the UK, especially among women, as can be seen in Figure 1.1. The Labour Force Survey disaggregates part-time employment by reason as follows:

- those who could not find full-time jobs

- those who did not want full-time jobs

- those who were ill or were disabled

- those who were students or were at school

We focus on those workers who could not find a full-time job as our first indicator of underemployment.

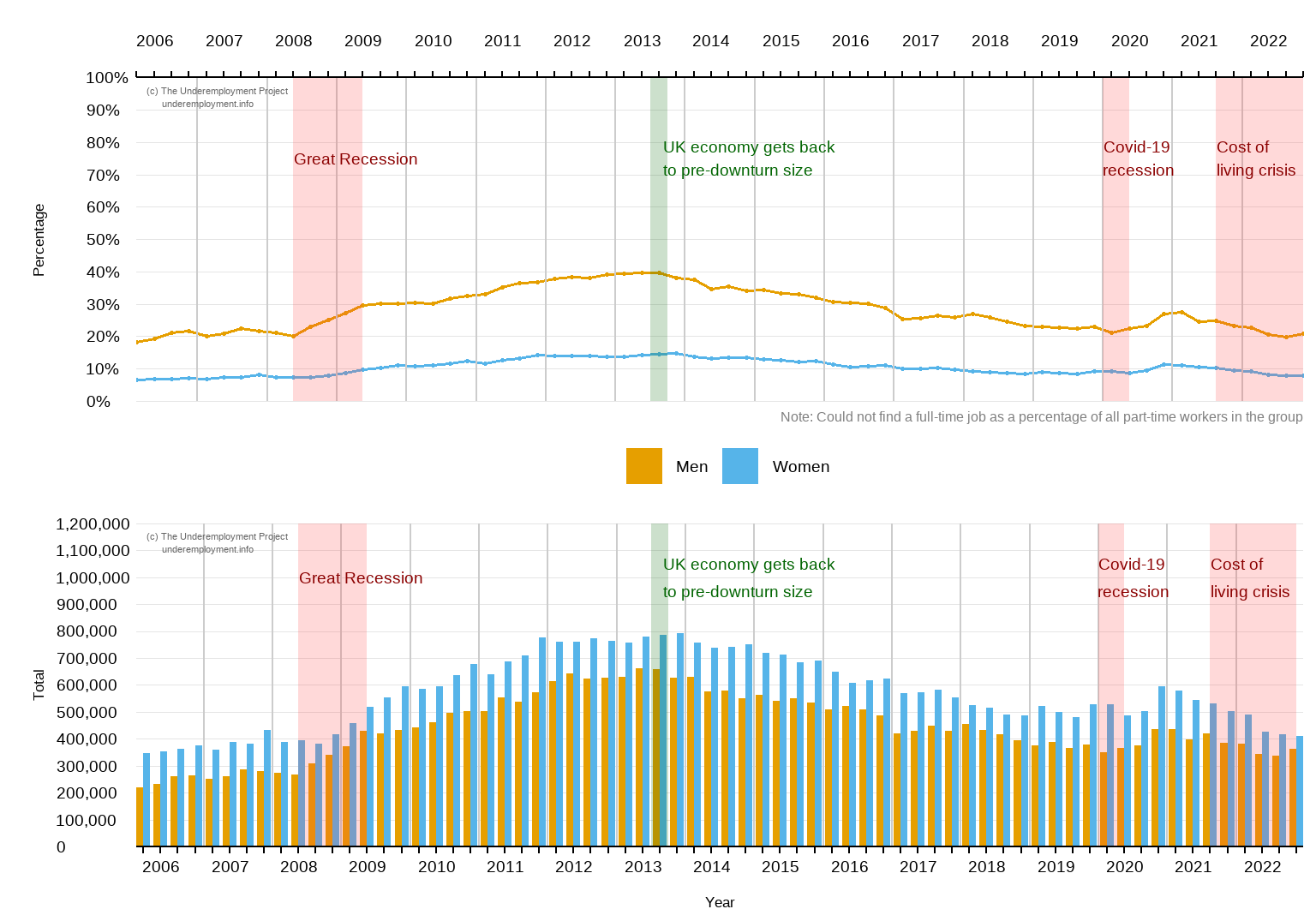

1.1.1 Time-underemployed part-time workers by sex

More female than male workers in the UK are employed part-time. Figure 1.1 shows which of those part-timers work part-time because they could not find a full-time job. In absolute numbers, there are more female part-timers in this situation (see bottom figure in Figure 1.1). One contributing factor is that, even after taking into account the gender of workers, underemployment is more common in female- dominated occupations, and less prevalent in male-dominated occupations and industries. The percentage of part-timers unable to find full-time work is significantly lower for women than it is for men: it is around 10% in most periods for women compared with a range from 20% to 40% for men (as shown in the top figure of Figure 1.1). Most female part-timers say they do not want full-time jobs, whereas the majority of male part-timers desire full-time employment but cannot find it. A key factor contributing to this disparity is that women often work part-time to fit around other roles in their lives, including caring for children and others (Warren and Lyonette 2018).

FIGURE 1.1: Part-time workers who could not find a full-time job by sex

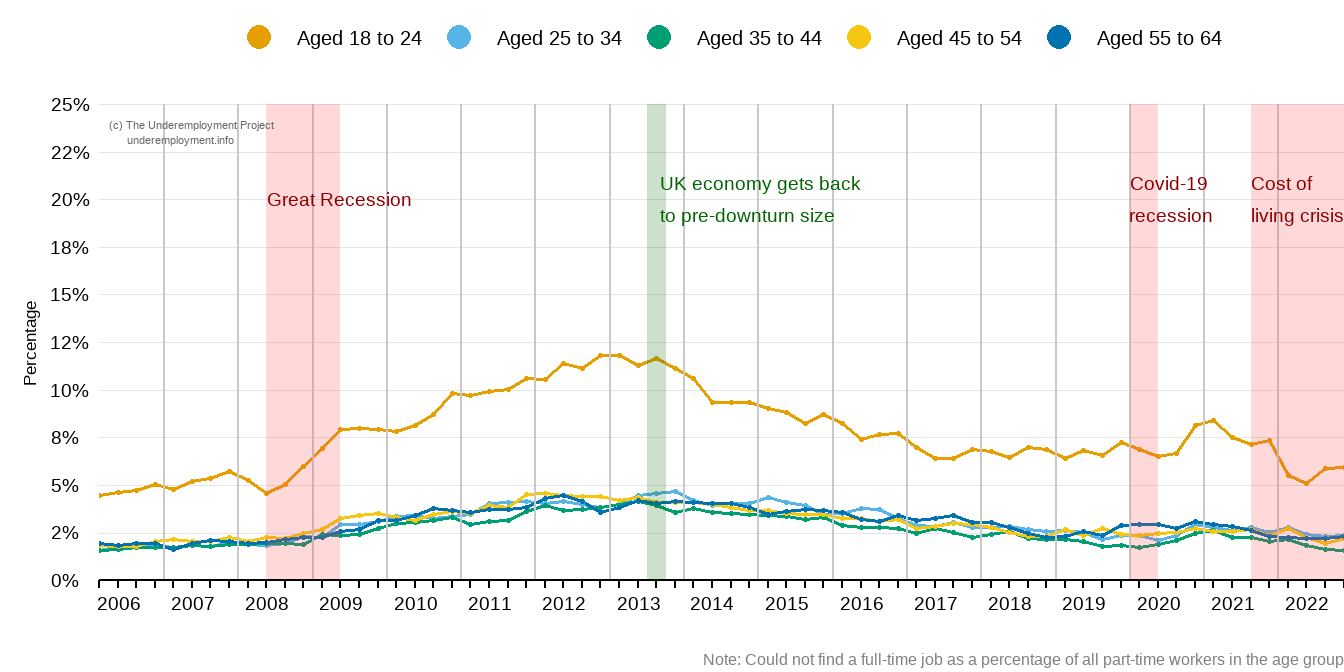

1.1.2 Time-underemployed part-time workers by age group

Figure 1.2 shows the part-time workers who could not find full-time work divided by age groups. Part-timers aged between 18 to 24 years old were most likely to find themselves involuntarily working part-time. Time-underemployment among the young increased following economic recessions (in 2008-9 and 2020) but the ongoing cost of living crisis from 2021 has not yet significantly worsened involuntary part-time work for this age group. Trends over time show similar peaks and troughs for other age groups, albeit with notably lower levels of involuntary part-time employment.

FIGURE 1.2: Young part-time workers struggle the most to find full-time jobs

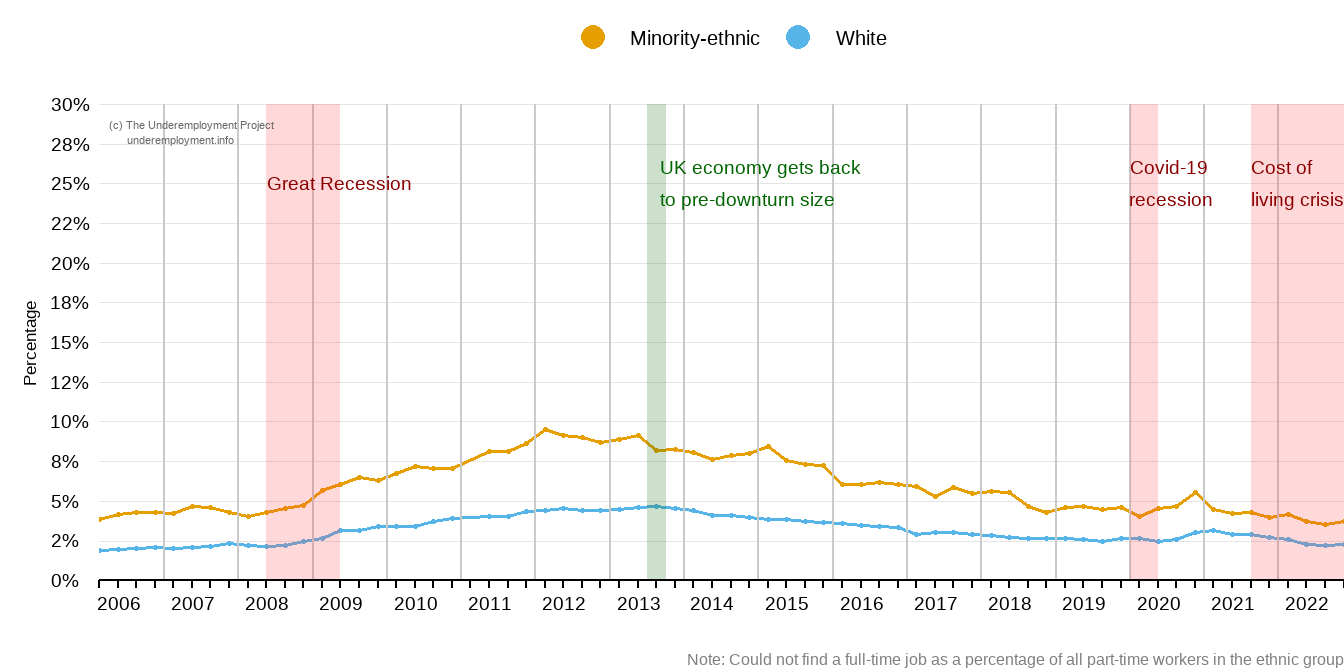

1.1.3 Time-underemployed part-time workers by ethnic group

Work-time in the UK is shaped by ethnic background. Figure 1.3 shows that part-time workers from minority-ethnic groups, grouped together, are more likely to work part-time involuntarily than are white workers. During the period under study both groups experienced similar trends with increases in underemployment following recessions and decreases during economic recoveries. However, minority-ethnic groups were disproportionately affected during recessions, experiencing a larger increase of involuntary part-time work than white groups after each economic crisis.

FIGURE 1.3: Ethnic-minority groups more likely to find themselves in involuntary part-time jobs

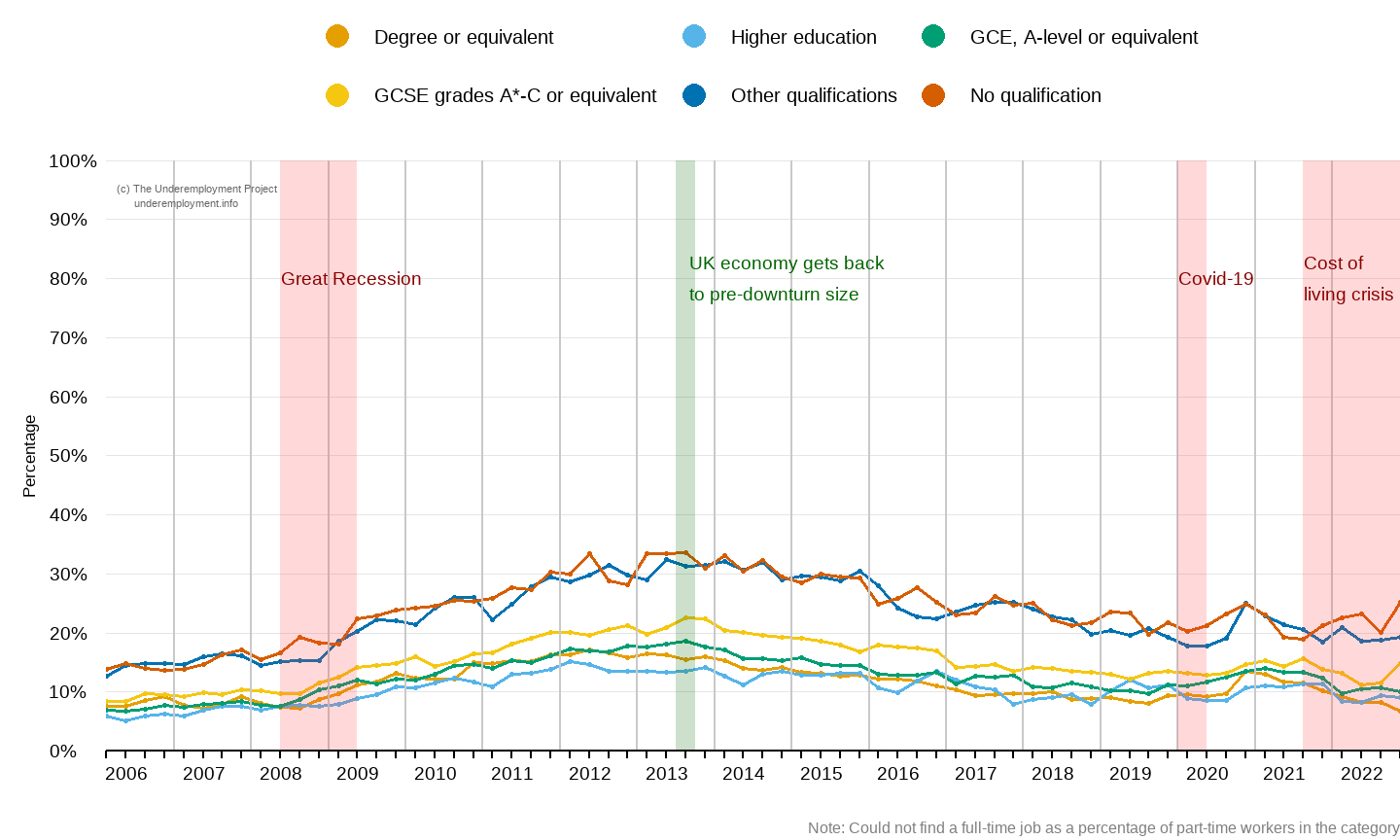

1.1.4 Time-underemployed part-time workers by qualification level

Qualification levels are a key factor shaping who is time-related underemployed. Figure 1.4 shows higher rates of involuntary part-time working among lower/no qualified part-timers. This suggests that across all years of our analysis, workers with no qualifications or lower-level qualifications find it more difficult to find full-time employment than do those with higher qualifications.

FIGURE 1.4: : Workers with no formal qualification find it difficult to find full-time work

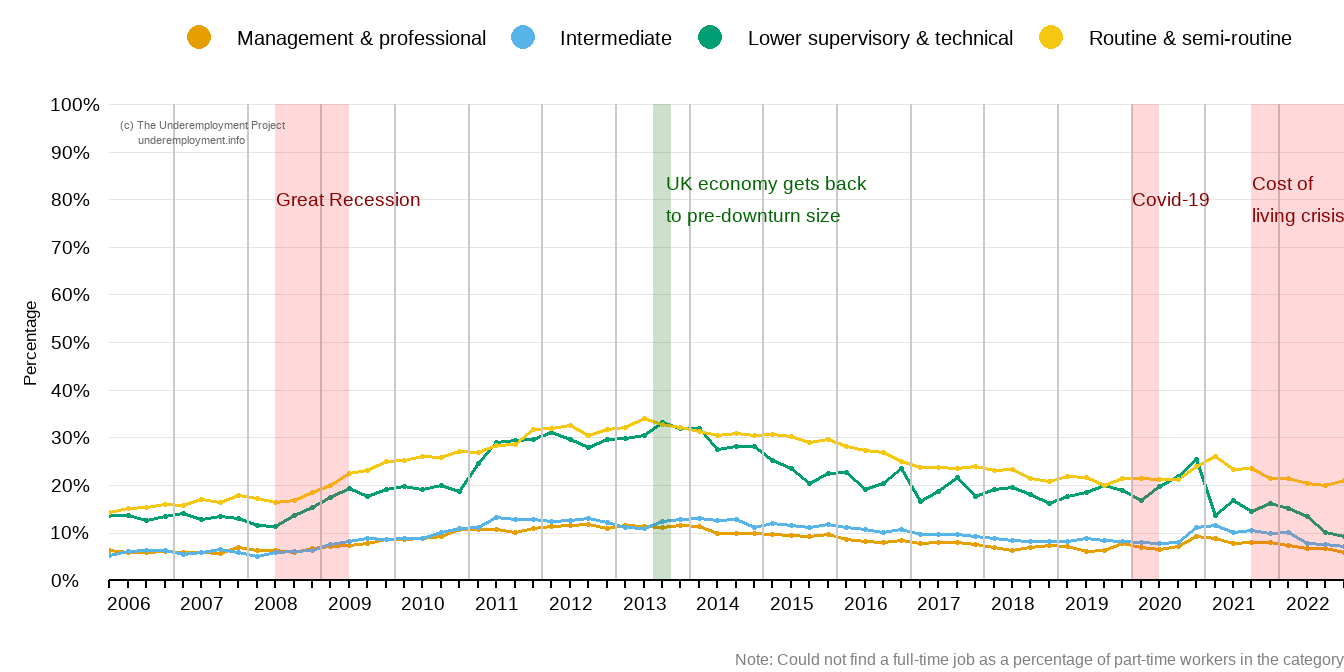

1.1.5 Time- underemployed part-time workers by occupational group

Part-time employment is concentrated in lower waged occupations, and with fewer opportunities to work part-time in more senior positions. Figure 1.5 shows which occupations feature the most involuntary part-time working among part-timers. Routine occupations (e.g., HGV driver, van driver, cleaner, porter, packer, sewing machinist, messenger, waiter or waitress, or bar staff), semi-routine (e.g., postal worker, machine operative, security guard, caretaker, farm worker, catering assistant, receptionist or sales assistant) and lower supervisory/technical (e.g., motor mechanic, fitter, inspector, plumber, printer, tool maker, electrician, gardener or train driver) stand out with higher rates of time-underemployment than managers/professionals and those in intermediate roles. Economic downturns affected these groups the most too, intensifying their underemployment.

FIGURE 1.5: Routine, semi-routine and technical part-timers more likely to be in involuntary part-time work

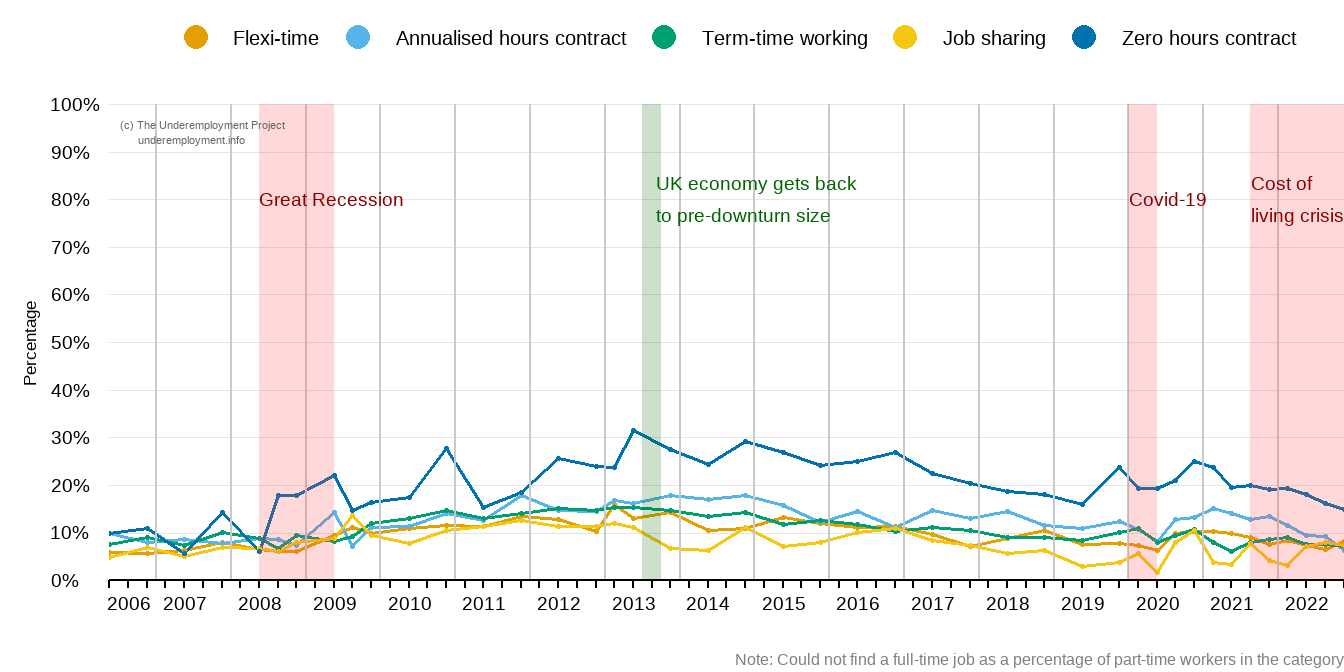

1.1.6 Time-underemployed part-time workers by contract type

In recent years, the UK has seen a decline in the number of employees with a so-called ‘standard employment relationships’, characterized by a secure and full-time job contract with their employers. The proliferation of alternative contract types, such as flexi-work, term-time working, raises many questions about the quality of that work and workers’ experiences. Perhaps the most contentious form of work, especially relevant for our focus on temporal underemployment, is the zero-hours contract, in which workers are not guaranteed any hours of work at all from their employer. Zero hours contracts give employers a great deal of flexibility, but there is debate over whether workers opt positively into zero hours jobs for flexibility themselves or must agree to such precarious work in a limited labour market. We show here that part-timers with more precarious contracts are more likely to be in part-time work because they could not find a full-time job than are other workers (Figure 1.6: workers with zero-hours contracts have had the highest levels of involuntary part-time work since 2008.

FIGURE 1.6: Workers in zero hours contracts struggle more to find full-time work

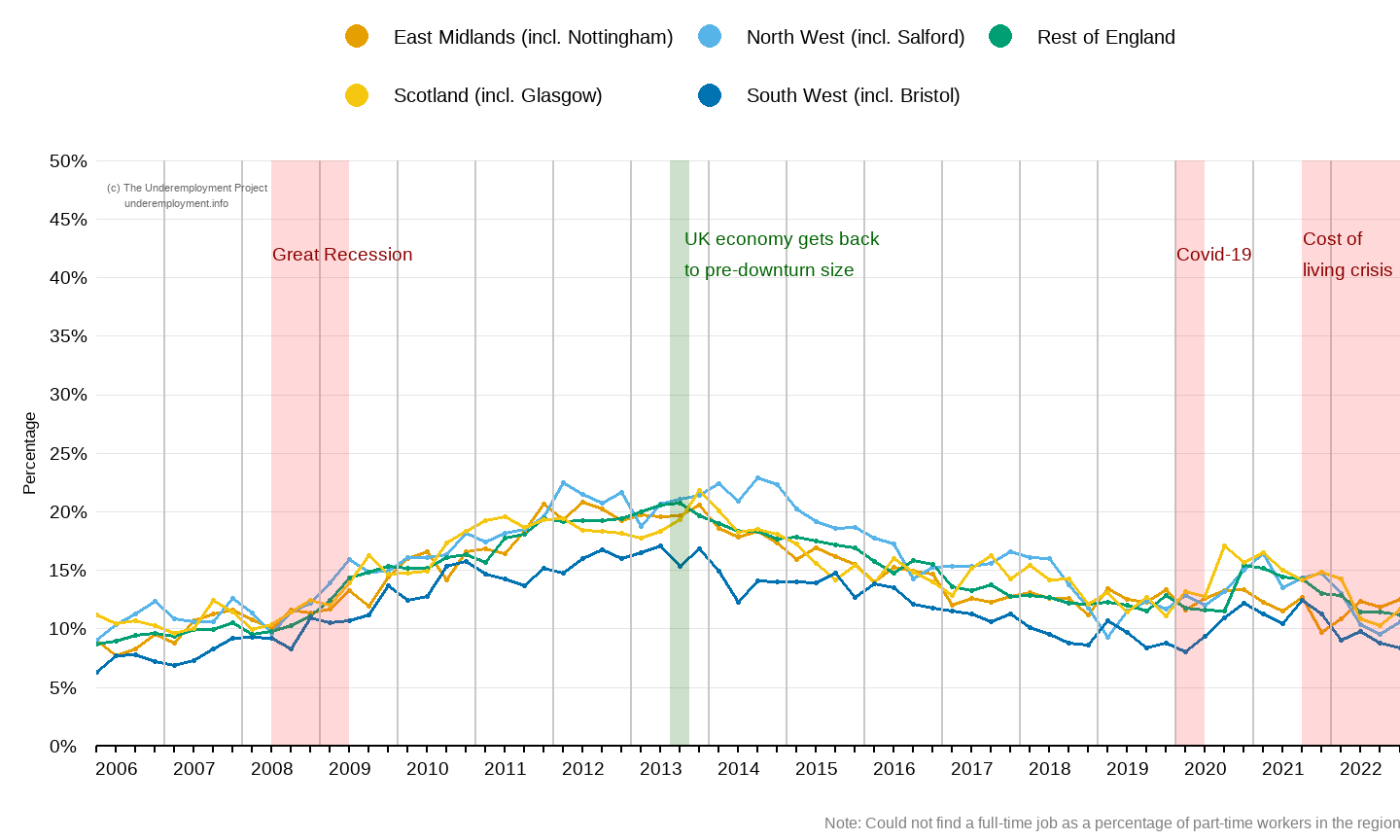

1.1.7 Regional trends in time-underemployment among part-time workers

Our project provides analysis of underemployment across the UK, but it focuses too on the four cities of Bristol, Glasgow, Nottingham and Salford. Figure 1.7 shows the distribution of workers in involuntary part-time employment in regions of England and Scotland that are in the scope of this project plus the rest of England. The North West of England (including Salford) and Scotland (including Glasgow) have the highest proportion of workers working part-time because they could not find a full-time work, while the South West (including Bristol) consistently has the lowest proportions, and this pattern has remained consistent over time . Meanwhile, the East Midlands Region (including Nottingham) saw an increase in involuntary part-time working during 2022.

FIGURE 1.7: Workers in the North West of England and Scotland struggle more to find full-time work

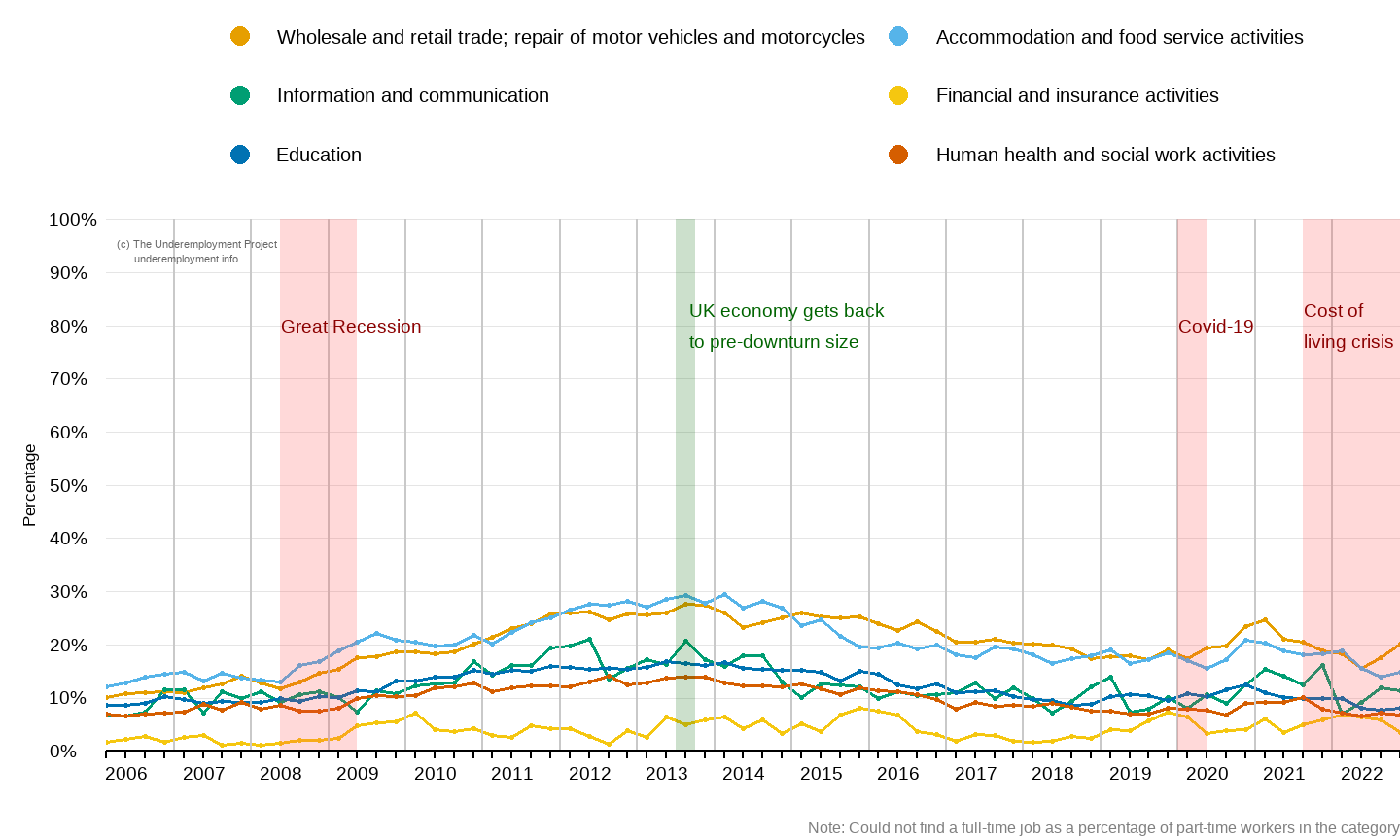

1.1.8 Industry trends in time-underemployment among part-time workers

In addition to its concern with underemployment across the whole labour force in the UK, the project focuses upon two industry sectors: Wholesale and retail trade, and Human health and social work. We are examining the extent of diverse and intersecting forms of underemployment there and the lived experiences of workers. Figure 1.8 shows the distribution of workers in involuntary part-time in six service-related sectors. Involuntary part-time work is particularly prevalent among part-timers employed in the Retail as well as Hospitality (accommodation and food service) sectors, justifying their inclusion in our research going forward. Human health and social work activities show lower levels compared to the two sectors mentioned above, and similar rates with sectors such as Education. Very few part-timers working in finance and insurance are doing so involuntarily.

FIGURE 1.8: Involuntary part-time is high in the Retail and Hospitality sectors